Today is Memorial Day, a national day of remembrance for members of our military who have died in service to this country. It was first observed as Decoration Day, commemorating those killed in the American Civil War, a number estimated at between 620,000 and 750,000. During my childhood, Veterans' organizations passed out paper poppies on Memorial Day, a tradition inspired by WWI, but it seems that practice has been lost because I haven't seen them for many years.

I've known only two people who were killed in battle. A neighbor died in Viet Nam in the early days of that conflict. I didn't know him well. He was older than I, but I never forgot him. On a trip to Washington, D.C. decades after his death, I found his name on the wall of the Viet Nam Veterans Memorial. My fingers swept across the polished granite, feeling the weight of all those carved letters —58,272 service members killed or missing, many more than the total population of the town where I was born.

The second was my great uncle, Julius, who was killed in WWI in the Argonne on October 9, 1918 one month and two days before the Armistice. While he was gone long before I was born, my mother, who was the keeper of family stories, preserved his legacy in our collective memories. His history is not unlike other soldiers who are serving in our military today: He was an immigrant. Julius was born in Russia to German parents who came to the U.S. to find a better, safer life. He was from a large family of hardworking people who were grateful to be living in the U.S.

Julius was a corporal in the 364th infantry, 91st division. He had been in France for only four months when he died. Colin V. Dyment described Julius’s death in a letter to his mother.

"In the Argonne men of the 91st not infrequently turned to a comrade close by, only to find him gone west, killed so quickly that he had neither moved nor uttered a sound."

He was buried in France next to several of his friends. In his pocket they found a letter to his mother that he had written in pencil two days earlier. It was removed from his clothing before he was buried and anchored on top of the grave with a rock.

A fellow doughboy found the letter sometime later, stained by mud and rain. There was no address just a reference to Julius’s hometown. The soldier carried the letter with him for eight months until he returned to the United States and tracked down Julius's parents, my great grandparents. Julius’s last letter is still in our family grab bag of relics from the past. I share part of that letter today because his words seem poignant and universal.

"Tell everybody hello for me and to write to me, even if I don’t write. I don’t get much time. I’ll have lots to tell when I get home. I have been through just about all of it once and I have a pretty good idea what it is now…Mother, it is getting dark and we are about to move to another place, so I’ll have to close. Don’t worry about me. I am sure the Lord is with me and that He will stay by me to the end. If it be His will that I stay here, I know that we will meet again in a better land where there is no war."

Dear Uncle Julius,

I hope you found that land where there is no war and please know that even ninety-five years after your death, your family still remembers you with tears of grief and pride.

Love,

Patty

Lovely tribute. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Bonnie. It's good to remember what this day is really about.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for sharing that powerful, moving family story, Patty. Happy Memorial Day to you.

ReplyDeleteThanks for stopping by Kathryn and same to you.

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely stunning. Thanks, Patty.

ReplyDeleteA good friend of mine who helped lead the first Americans into the French trenches of WWI always had a glass of port on Nov. 11. He lived a long time with shrapnel wounds but made it to age 104.... still missing his friends from the US Army. He survived the trenches only because he was blown up and tossed into an old shell crater while others were killed on either side of him. Maybe one was your relative.

What a great story, Alice. Next year I'm going to sip a glass of port as I remember Julius and your friend.

DeleteMy dad fought in WWII and went to many reunions with his Army buddies. He never talked much about the war, except maybe to them. It's a shared experience that's difficult for the uninitiated to understand. Lovely hearing from you.

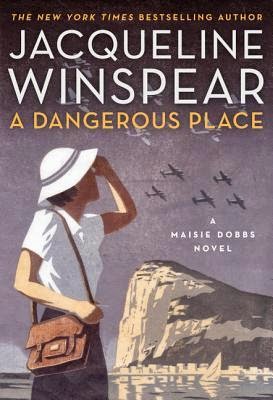

from Jacqueline

ReplyDeletePatty, only just read this post - and thank you. Poppies are still worn in Britain, but on November 11th, to commemorate what was once known as "Armistice Day" and is now known simply as "Remembrance Day" - when the dead of all wars are remembered across the land. Other "Commonwealth" countries commemorate the same day, "Lest We Forget." I took out last year's poppy and put it on my desk yesterday. I think we will all remember Uncle Julius now.

Our November 11 celebration is Veterans' Day, during which we honor all veterans, living or dead. Memorial Day is for those killed in wars. But you've jogged my memory. I think the poppies were handed out in November. Still, haven't seen them in years.

DeleteWhat a touching last letter your uncle wrote, Patty. Thank you for sharing it.

ReplyDeleteI used to look at wars this way, when my son was little--how would I feel if he fought in a particular war and got killed? Was that war worth his death? And then, lo and behold, my son grew up and developed into a career officer in the US Army.

Not too many wars can stand up to that test.

I've begun calling myself this...pro-soldier and anti-war.

That was the one lesson learned from the Vietnam War, it seems to me. Separate the soldiers from how you feel about the war. Some men I know are still suffering from how they were treated when they returned from the war. It's awful. I hope the lesson stays learned.

ReplyDeleteBeautifully stated, Kay. And let's remember, most of those Viet Nam vets were drafted.

Delete