The Benefits of Research by Lisa Black

One of the best and worst parts of writing a book is doing the research necessary to bring authenticity and realism to your plot. The worst, because we left school behind (sometimes) long before and yet here we are doing homework. The best, because we can do something other than write and still feel that we are virtuously working toward a great tome—and because we pick up some really interesting facts. Over the years I have read about life during the Great Depression, the history of video games, and how to mix up plastic explosives in your own garage. Good stuff.

In the next book I decided to make my main character a former foster child. (This may be becoming a trend, just as all detectives used to be recovering alcoholics, Vietnam war vets, or children of murdered parents.) So I dutifully began to research foster children. This is unusual because—full disclosure—I do not like children. I bear them no ill will, but they make me nervous, which is why I never had any. Well, that and because my husband is a child and trying to raise one with him would have committed me to twenty years of daily battle.

It will come as no surprise that the foster child care system is a mess. What may come as something of a surprise is that this is not really anyone’s fault. Social workers can be overworked, underpaid and burnt out. Foster parents can be all over the board in terms of what a child needs and whether or not they can provide it. Foster children can be ungrateful and unrealistic. Biological families can be irresponsible and irreparable. But even if each cog in this system worked to the utmost of their ability, the situation would still largely stink, because no matter what else occurs a child’s life and attachments have been disrupted and that creates a very lasting wound.

Obviously the most important goal is safety. But only about 25% of children are removed due to some sort of abuse; the other three-quarters are removed for ‘neglect’ and the case can be made that neglect is simply another word for poverty. There may be cockroaches in every corner, nothing but junk food in the house and the kids haven’t taken a bath in three days, but, a parent could counter, they grew up the same way and they survived. It may not be the way we think a child should be raised—and we all, myself definitely included, think we know the way a child should be raised—but it’s hardly grounds for removing the child from the home. Or take a single mother who leaves her three- and six-year-olds home while she works. She’s not out at a rave or taking drugs, she’s working to keep them fed and housed. Yet three and six are too young to be home alone, period. So, what to do.

Foster parents, meanwhile, and contrary to popular belief, very rarely take on the role ‘for the money.’ There is not nearly enough money involved to make it worth it. Most begin this work because the children were relatives and they couldn’t let their kin go to strangers, or they do it because their parents did it and they know the importance of maintaining their community, or they do it because it’s the right thing to do. It’s a hell of a risk, bringing a total stranger into your home. Even if you have a perfect nice set of foster parents and a perfectly nice foster child, a removal can occur because of personality conflicts, space problems, because the child has some sort of special need and has to move to another agency or district, and so on, and each move reinforces to the child that they are unloveable and unwanted. They quickly learn not to get attached to anyone or anything, because it could all change in the next hour. And if a child can’t form attachments, a process vital for their development, then foster care has no purpose—

I don’t see a solution and neither does anyone else. No policy or structure or social planning can change the fact that human beings are messy, complicated, inconsistent and unique.

All we can do is try.

Her new novel is Close to the Bone

Close to the Bone

hits forensic scientist Theresa MacLean where it hurts, bringing death and

destruction to the one place where she should feel the most safe—the medical

examiner’s office in Cleveland, Ohio, where she has worked for the past fifteen

years of her life. Theresa returns in the wee hours after working a routine

crime scene, only to find the body of one of her deskmen slowly cooling with

the word “Confess” written in his blood. His partner is missing and presumed

guilty, but Theresa isn’t so sure. The body count begins to rise but for once

these victims aren’t strangers—they are Theresa’s friends and colleagues, and

everyone in the building, herself included, has a place on the hit list.

Thanks, Lisa. Your books show your research and your talent. Great read!!

ReplyDeleteWhat James O said! Glad to have you with us.

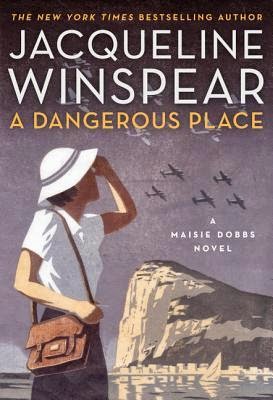

ReplyDeletefrom Jacqueline: Great post! And it speaks to something many of us experience - not only do we write about and research those issues that we find compelling, but through our research we become passionate - for me, delving into the history of treatments inflicted upon women suffering from real or perceived psychiatric illness made me raw with grief and anger. Though it comprised only a small part of the story in my novel AMONG THE MAD, it was important for me to immerse myself in the truth of what was endured. We learn so much - and perhaps getting mad about the issues we research helps us to reveals the truth - and truth is often more readily portrayed in fiction than in fact.

ReplyDeleteYes! In this busy world, researching something for a book gives us the opportunity to get deep into one topic at a time.

ReplyDeleteMakes you wonder why we don't see more writers on Jeopardy! I bet we'd be great!

The world of foster care surely needs examining...in both fiction and non-fiction. Great piece! Thanks, Lisa.

ReplyDeleteThis is a really good post but similar to Thursday's.

ReplyDelete